Traveling to History: Twenty Four

The Innocent, the Damned, and Daniel Webster: Salem was the scene for an infamous murder trial.

By James F. Lee

Courthouse Square in Salem. The White murder trial was held on the second floor. This building was demolished in 1839.

A Cold-Blooded Murder

On the morning of April 7, 1830, in Salem, Massachusetts, the body of Captain Joseph White was found by a servant, bludgeoned and pierced with 13 stab wounds. White, a wealthy, widowed merchant, had been murdered in his bed. Salemites were aghast; if an innocent octogenarian wasn’t safe in his bed, then who was?

Even more shocking, four young men from two of Salem’s most prominent families were charged with the murder: brothers Richard and George Crowninshield, and brothers Joseph, Jr., and Frank Knapp.

Jealousy was one motive for the murder.

Portrait of Captain Joseph White, 1824, by James Frothingham. This was painted just six years before White’s death.

Joseph White and his wife Elizabeth Stone White were childless and over the course of their marriage had adopted several nieces and nephews. Elizabeth died in 1822. At the time of the murder, two of their adoptees survived: the cousins Stephen White and Mary (Ramsdell) Beckford. Stephen White was a prominent Salem merchant and political leader, who lived in an elegant brick mansion by the Salem Common, while Mary Beckford, a sea captain’s widow with four children, kept house for her uncle. It wasn’t lost on Mary that she was several steps down from her cousin.

The other motive was greed.

In 1827, Joseph Knapp. Jr. married Mary Beckford’s 17-year-old daughter, Mary. Both Captain White and Stephen White heartily disapproved of the marriage, particularly because of Knapp’s unsavory reputation.

Fearful that Stephen White would inherit the bulk of Captain White’s estate, Joseph Knapp Jr. believed that a pre-existing will was more favorable to his mother-in-law. He planned to murder White and destroy his latest will, guaranteeing a large inheritance to his side of the family. He offered Richard Crowninshield $1000 to do the deed.

Today’s Gardner-Pingree House. Captain White was murdered in his bedroom on the second floor, left windows.

A Media Circus

The primary suspect, Richard Crowninshield, accused of the actual killing, committed suicide in his cell at the Salem Jail. This created a major legal obstacle for the prosecution because accessories to crimes (in this case the other three defendants) could not be tried if the principal were not convicted – and the principal was dead.

The three defendants in the White murder trial.

The remaining defendants would be tried separately. Frank Knapp’s trial came first because of his proximity to the crime scene: he had waited on Brown Street behind White’s house while the deed was done and helped hide the murder weapon.

Eager crowds thronged the second floor of the Salem Courthouse on Washington Street. Enterprising people set up refreshment stands in the square in front of the courthouse. Reporters raced to get each day’s proceedings into print.

A floorplan of the Joseph White house. White was murdered in the bedroom above the Keeping Room.

Chief Justice Isaac Parker of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, presiding over the trial, decried the media circus as a threat to justice.

A grand jury indicted the three defendants on July 16. Nine days later, Parker died of a stroke, leaving a panel of three judges to hear the case, including Samuel Putnam of Salem as senior judge.

The trial reconvened on August 3rd. Parker’s death gave the prosecution time to consider its options. They needed help, so they turned to the most prominent lawyer they could find: Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, a close friend of Stephen White. Earlier that year, Webster electrified the nation with a speech in which he proclaimed, “Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable.” Although Webster was not much experienced as a capital trial lawyer, the prosecution reasoned that his formidable rhetorical skills would run circles around the defense.

After ten days of testimony, the trial ended in a hung jury. A new jury was quickly called, and now Webster pulled out all his oratorical stops.

The Banality of Evil

Map of the important scenes in the crime. White’s house is labeled “J” and the Howard Street Church “A.”

Webster argued to the jurors that the law must punish the guilty in order that all innocent people may remain safe.

“It is said that ‘laws are made, not for punishment of the guilty, but for the protection of the innocent.’ This is not quite accurate, perhaps, but if so, we hope they will be so administered as to give protection. But who are the innocent, whom the law would protect? Gentlemen, Joseph White was innocent,” he said.

This 1851 map of Salem gives a sense of the small world that Salem was at the time. White’s mansion is labeled “D. Pingree” just above the X is “Essex.” The Howard Street Church is located at the southern end of the Howard Street Cemetery. And the County Jail is just to the left of the cemetery.

And he stunned them with his portrait of the nonchalance with which the conspirators carried out the murder.

“This bloody drama exhibited no suddenly excited, ungovernable rage. The actors in it were not surprised by any lion-like temptation springing upon their virtue, and overcoming it, before resistance could begin. Nor did they do the deed to glut savage vengeance, or satiate long-settled and deadly hate. It was a cool, calculating, money-making murder. It was all ‘hire and salary, not revenge.’ It was the weighing of money against life; the counting out of so many pieces of silver, against so many ounces of blood.”

There was forensic evidence as well. In a jailhouse confession, Joseph Knapp, Jr. said that one of the murder weapons, a two-foot-long club, was hidden under the stairs at the Branch Meeting House next to the Howard Street Cemetery, across the cemetery from the Salem Jail. Presumably it was placed there the night of the murder when Richard Crowninshield met Frank Knapp on Brown Street behind White’s house.

At any rate, Webster won the first case. Frank Knapp was hanged in the prison yard on the north side (facing Bridge Street) of the Salem Jail. This hulking granite edifice still stands on Saint Peter Street, practically around the corner from the scene of the crime.

This 1820 map shows the location of the courthouse (labeled #2) in the middle of Court Street (now Washington Street).

Joseph Knapp followed his brother to the gallows several months later. Both brothers were buried in unmarked graves in the Howard Street Cemetery, the same cemetery where their victim was buried. Only George Crowninshield was acquitted, based on the testimony of prostitutes with whom he spent the night of the murder.

The White murder trial was a sensation, generating nationwide newspaper coverage and contributing to Webster’s fame as a spellbinding orator. But the significance of the trial doesn’t end there. Webster brought victims’ rights into stark relief. His picture of a remorseless murderer became an early image in an American tapestry of crimes committed by emotionally numb killers who might look like the boy next door.

In a stifling courtroom in Salem, Massachusetts, Webster showed us the benign face of evil.

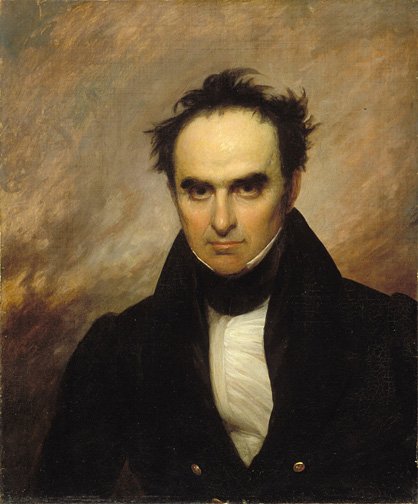

Portrait of Daniel Webster about four years after the trial.

The Scene of Events

Salem was a small town in 1830. Many of the principals in the Joseph White murder case were close neighbors and several of the sites are still standing within a very short walk of each other.

CAPTAIN JOSEPH WHITE’S HOUSE, 128 Essex Street. Known as the Gardner-Pingree House, this beautiful three-story brick federalist mansion is open to the public, including the room where White was murdered. Visitors can also stroll the grounds and see the rear window where Richard Crowninshield entered the building. The house is owned and operated by the Peabody-Essex Museum (PEM).

THE SALEM JAIL, 50 St. Peter Street. Built between 1811 and 1813, this massive granite block building still stands prominently at the corner of St. Peter and Bridge Streets. It was one of the longest serving penal institutions in the country before it closed in 1991. Today, the building has been redeveloped into apartments. But standing outside the building gives you an idea of how foreboding the place might have once been.

A view of the old Salem jail.

HOWARD STREET CEMETERY, Howard Street between Bridge and Brown Streets. This ancient burying ground adjacent to the jail and withing 100 yards of the murder scene contains the tomb of Captain Stephen White. Also buried here in unmarked graves are Richard Crowninshield and the Knapp brothers. The Branch Meeting House where the murder weapon was found no longer stands. It was located next to the cemetery near the corner of Brown Street.

The Howard Street Cemetery with a view of Salem Jail in the background. Both Knapps were buried here in unmarked graves. Their victim, Captain White, is buried here as well.

STEPHEN WHITE HOUSE, 31 Washington Square, North, at the corner of Oliver Street. This brick federalist mansion across from Salem Common was the home of Captain White’s nephew and beneficiary Stephen White. It is notable for its rectangular front porch with four white Corinthian columns. Given its location, it is conceivable that Stephen White could have looked out his window towards the Common, where the conspirators met on one of the nights before the murder. The house today is divided into private residences.

Stephen White’s mansion on Washington Square North, just a short distance from his uncle Joseph’s house. Today it is private residences.

JUDGE PUTNAM’S HOUSE, 138 Federal Street. Samuel Putnam, one of the judges presiding over the murder trials, lived on Federal Street in what is today known as the Cotting-Smith Assembly House. Built in 1782, it was originally a public lecture and concert hall and ballroom with a fiddlers’ gallery. George Washington was entertained here at a ball in 1789. By the time Putnam purchased the building, it had been redesigned as an elegant mansion in the federal style with Ionic pilasters and a pediment above. The building can be rented from the PEM for events.

This was the Federal Street home of Samuel Putnam, a judge in the Joseph White murder trial. Today it is owned by PEM and available to be rented for events.

THE OLD SALEM COURTHOUSE. Much of this story takes place in a building that no longer exists. This two-story structure stood at the head of Washington Street literally in the center of the street. It was an imposing building with a hipped roof, Greek Revival portico, and a two-story cupola. Its front faced Town House Square and the rear looked towards the North River. The court room where Webster argued for the prosecution was on the second floor. It was demolished in 1839 and replaced by the adjacent beautiful granite Greek-Revival Courthouse that still stands at the corner of Washington and Federal Streets.

THE KNAPP FAMILY HOUSE. 83-85 Essex Street. Another site no longer extant. The three-story Federal that stood at the corner of Essex and Orange Streets was the home of Captain Joseph Knapp, Sr., the Knapp brothers’ father. Its location gives a sense of how close everything was in 1830 Salem, just several blocks from Joseph White’s House. Today, visitors can admire the Georgian Colonial John Hodges House across Orange that was contemporary with the Knapp Houe.

SOURCES

Lewis Walker, “The Murder of Captain Joseph White: Salem, Massachusetts, 1830.” American Bar Association Journal, May 1968.

Daniel Webster and the Salem Murder. Bradley and Winans, Columbia, MO: Artcraft Press, 1956.

American State Trials, Vol. VII. “The Trial of John Francis Knapp for the Murder of Joseph White. Salem, Massachusetts, 1830.”

PHOTO CREDITS

Courthouse Square, oil on wood panel, 1820, by George Felt, Peabody Essex Museum, from photo, File:View of Courthouse Square.jpg - Wikimedia Commons{{PD-US}}; White portrait, Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum, photo by Kathy Tarantola/PEM; Gardner-Pingree House, Elizabeth B. Thomsen, own work, CC-SA 4.0 Creative Commons — Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International — CC BY-SA 4.0; three defendants, image from Bradley and Winans; floorplan, image from Bradley and Winans; 1851 Salem map, by H. McIntyre, reproduction courtesy of Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library (BPL); map of important scenes, from Bradley and Winans; 1820 map, by Jonathan Saunders, Leventhal Center, BPL; Daniel Webster portrait, by Francis Alexander, author Dak06 {{PD-US}}; Stephen White’s mansion, photo courtesy of Patricia Kelleher, Preservation Planner, City of Salem, MA; Samuel Putnam’s house, Fletcher6, own work, CC-SA 3.0 Creative Commons — Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported — CC BY-SA 3.0; Salem Jail, and Howard Street Cemetery, photos by Rebecca Brooks.